But Finchingfield meant more than a motor-bike and sidecar, exciting though it was to ride pillion, short young arms clinging round Uncle Bert's leather-jacketed waist. It meant pungent woodsmoke; prolific cats with prodigious litters of kittens mewing in the logshed; rabbits cavorting in the meadow at dusk beside the cottage; and carrying, in the early morning, pails of cold, crystal-clear water from the spring. To my parents, Finchingfield meant parsnip wine, country and cheerful evenings of conversation in the oil lamp's glow.

In 1944, my wife and I sought Finchingfield for our brief wartime honeymoon. American fighter planes flew from Wethersfield and peace was frequently, if temporarily, non-existent. And not only in the air! How my cousin John laughed when I repulsed two allied airmen, in true RAF fashion, as our party sauntered down the hill from the Green Man! He could be amused, but we'd been married a mere 24 hours.

After the war, the Americans were still much in evidence, and now it seemed that every available vacant cottage was theirs. I hope the villagers' material living standards rose in consequence, as in many other villages in many other lands temporarily ceded to Uncle Sam. Had happiness kept pace?

In those days it was a rural trait to be aware of all who passed by. Nosiness? But one can die unnoticed in a town. Nevertheless, villagers today must have a desperate job carrying on the custom. For Finchingfield in summer is Mecca in Essex. Cars litter the village, and the green that rises from the duck pond, past the war memorial, to elegant houses by the chapel and the old school, swarms with visitors. So many summers ago I played in peace with Eric and Eileen whose father ran the local bus service. It was safe then to kick a ball into the road, or chase a hit to square-leg down to the water. It would be certain death now. Then in safety too, one could lean over the narrow humped-back bridge by Linsell's store and watch a pony and trap ford Finchingfield's picturesque pond.

Yet who could deny these Finchingfield folk their share of the fruits of progress? Or their right to a living - and a bit more if they can get it - from the much publicised charms of their village? The dominating church, the chapel, the Fox, the Green Man, the butcher's shop, the Post Office, and the Causeway rim the bowl of Finchingfield, the photographers' phobia. Fear that it might change? The famous old windmill still stands, white and silent, reminding transient trippers that it, anyway, has a right to overlook these traditionally arable Essex acres.

I have good reason to remember those arable traditions. In about 1936, I spent a holiday with my cousin John at Duck End. It being harvest time, he took me to the customary rabbitting, when we youngsters encircled the cornfield and, as the harvester worked inwards, chased the fleeing rabbits. In those days, before myxamatosis, rabbit pie made a cheap and delicious meal. As usual, the farmer was there, armed with his shot-gun, and made it clear that he would get first crack at any rabbits running within his range.

The harvester approached us and suddenly a frantic rabbit shot out of the corn. I shot after it, egged on I thought by the yells of my companions. The rabbit escaped, I'm happy to say now. All I got was a right "royal" rocket from the farmer. Only narrowly had I missed the indignity of a load of buckshot where it would have hurt a 14-year-old most!

John and I agreed to forget it, but there are no secrets in a village. Uncle George, an invalid who made beautiful leather purses, merely berated his son for not looking after me well enough. Aunt Julia remarked that had the farmer been "chapel" instead of "church" such an incident could never have happened! The sole divisive issue in village life that I recall.

And what of Spain's Hall? Is it still mentioned in a voice of reverence and respect? Last summer I saw a notice announcing that, one Sunday, Spain's Hall would be open to visitors; proceeds in aid of SSAFA, a worthy cause. Presumably the Hall is not open every day, like Woburn Abbey. Here was a chance to fill another gap in my association with Finchingfield, for in all my visits I had never been nearer the Hall than the end of its majestic avenue of a drive. This ideal opportunity to tread holy ground, though not as it turned out to enter the Holy of Holies of my boyhood, was accepted.

I reflected that my father, when a boy, had made it his business to be at the drive every morning when the squire had ridden out, to be rewarded generously for opening the gate. I was disappointed that the house remained inviolate on that sunny Sunday afternoon, for it is human nature to wonder how the other half live - and lived.

I was glad, too, because invasion of my privacy is intolerable. My affinity for Finchingfield, however tenuous my connection with Spain's Hall, made inspection somehow distasteful. Here resided no ordinary gentleman. Here lived my personal chieftain. And my father's. And my grandfather's, at least.

Driving homeward, only one memory was clouded. One vital aspect of true village life remained hidden. Is there still cricket in Finchingfield? If so, where? At forty years' distance the geography is obscure. The only certainty is one miserable entry in an old scorebook when this particular Digby, despite the propaganda put about by his cousin John, had been bowled "neck and crop" first ball. Sad it is that this lovely village, from which my forbears went out to fulfil their destinies, of me records only a "duck". But perhaps the pitch was at Duck End!

Hopefully, the years have been kind to Finchingfield, for the dream that one day I should go back to stay is real. But Finchingfield's beauty is a byword. Estate agents make that point. Decisively.

Text ©1970s Arthur Digby.

Mary Fehl, now living in Denver, came across two articles printed in the "Braintree and Witham Times" which had been preserved by her sister. The first one dates from c.1963 and is about a small hamlet called Little London. It's a mile or so north of Finchingfield itself, but part of the parish.

Mary explains that the Harringtons were her family and it would have been her mother's uncle, better known as Tom Harrington, who was the 71 year old licensee of the Little London off-license. She says "as a child I spent many hours in the dark old rooms of the house when visiting Uncle Tom. My mother was born in a small house behind the off-licence and spent many hours with her grandmother Mary in the main house. I know it has changed with the off-license being rebuilt but when returning home to England I always drive by Little London and remember it as it was."

The crocuses are again revealing the secret of Little London the smallest hamlet in north-west Essex. Fifty years ago a horse-drawn brewer’s dray would make the nine mile journey once a fortnight from Great Dunmow to the off-licence in the village,

A dozen barrels would be rolled onto the oak stocks and tapped.

And in the gardens of the 23 cottages of this lonely hamlet the crocuses bloomed each spring. People attended the tiny one-roomed chapel…… Today only the off-licence and two cottages remain.

"The licence has been in our family for 63 years."

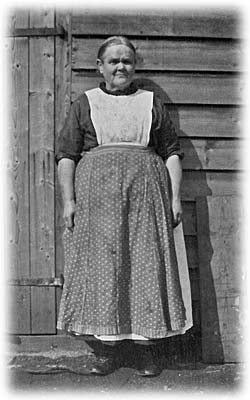

Oldest of 11 people living in Little London is Mrs. Betty Ridgewell, aged 78.

"I have been here about 48 years," she said. "The cottages became empty one by one, and nobody wanted to live here. The places just rotted until work-men pull them down."

"They wanted to pull down mine too but my husband wouldn’t let them because I had 11 children to look after."

Seven of the other members of the population, all members of the Ridgewell family, share the divided cottage.

The other is rented by an American Serviceman from the nearby Wethersfield air base.

Today the crocuses bloom, not only in the gardens of the last two cottages, but among the bushes and weeds where once stood the gardens of the 21 cottages which have vanished.

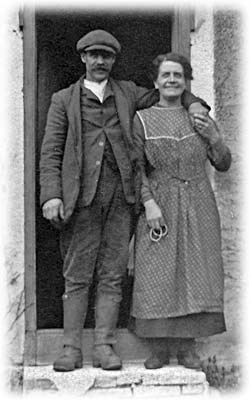

A corner of Little London in the 1930s.

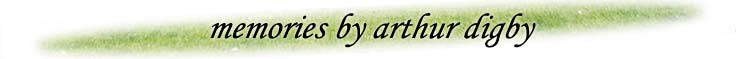

The second article sent by Mary features her grandfather, John Harrington, and dates from August 1960. John was born in 1880 and married in 1908. Spains Hall is an estate close to Finchingfield.

Strikes and disputes, walk-outs and lock-outs, "Coventry" and closed shops . . . they're everyday words in the language of modern industry. The "I'm all right, Jack" attitude.

But not at Spains Hall, Finchingfield, where cowman John Harrington worked for 65 years, where Joe Johnson is still employed after 60 years' service, where 90-year-old Jess Ralling only retired at Michaelmas, 1958.

And, of course, there are many more . . .

What's the secret of these long and friendly relationships between the Ruggle-Brise family and their employees?

Explained Mr. Harrington, who started work for Sir Samuel Ruggles-Brise, great grand-father of Sir John Ruggles-Brise, the present owner of the hall: "It is a grand family to work for and I would do it all over again if I had the chance. They have all been fine gentlemen."

Added Mr Ralling, who worked for three generations of the family: "I'm proud to have worked for them. I think the secret has been mutual trust and respect."

And Sir John himself said last week: "It is a tremendous source of pride to both my family and those employed by my family that we have a long list of people who have worked for us all their lives."

Respect and confidence in each other. Simple solution, isn't it?

For his ten or eleven-hour day, and for seven days a week, he was paid 2s 6d (12.5p). "We didn't think the days were long then," he said.

The Spains Hall herd of Jerseys - they averaged about 120 - were frequent winners in the show rings. And preparing selected cattle for these events was always something for the cowmen to look forward to.

Soon after he was married 52 years ago, he moved into one of the cottages adjoining the dairy. At that time they used to make about 350lbs of butter during the summer: a little less during the winter. It was posted to places all over England and the Continent, and it was Mrs. Harrington's job to weigh and pack the orders.

Mr. Harrington was head cowman for 50 years but eventually the herd was reduced and sold a few years ago. He was presented with a watch by the English Jersey Cattle Society in 1954 in recognition of 64 years' service with the Ruggles-Brise family.

Active all his life, he still is in retirement. He lives with his wife in a little cottage in the village and cycles to do odd gardening jobs.

Mr. Ralling was 30 when he came to Spains Hall to continue working on the land. Eventually he became manager of the 130-acre farm with instructions to "run it as if it were your own."

After the last war - when he was 75 - he became estate manager until just over a year ago, when his wife died. "She did all the book work," he explained. "I couldn't have done it without her."

But he can't stay away from Spains Hall. At least once a week he goes there and has tea with the cook and the butler - "and sometimes Sir John himself."

With John Harrington, Joe Johnson and dozens of others, he had tea at the hall again on Saturday, when Sir John gave his big party to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the ownership of the hall by his family.

It was more like a reunion of old friends.

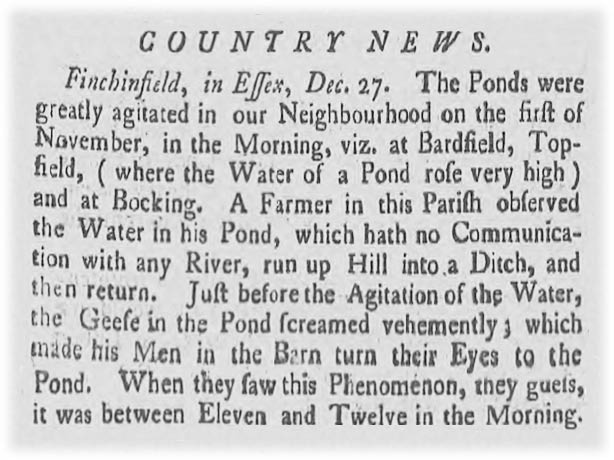

Here's a strange article which appeared in the Derby Mercury of 2nd January 1756